By Valerie Hansen

The Silk Road

Expanded College Edition

This new edition of the book is specially designed for use in the classroom. Based on the trade edition, The Silk Road: A New History with Documents offers a selection of excerpted primary sources at the end of each chapter.

A new chapter focuses on the route across the grasslands, which ran several hundred miles north of the traditional silk road around the Taklamakan. Several rich accounts written by travelers illuminate life on this route, which was used by the Mongols in the 1200s and 1300s. Although Marco Polo is the most famous Silk Road traveler today, others like John of Plano Carpini and William of Rubruck left more accurate accounts, and one traveler, Rabban Sauma, traveled in the opposite direction from Beijing to Europe.

The book also contains a total of 52 primary sources, including passages from the official histories, memoirs of medieval Chinese monks and modern explorers, letters written by women and merchants, marriage contracts and model divorce agreements, poems, descriptions of towns, legal contracts, and religious hymns, among others. About three quarters of the translations are drawn from existing translations (with any archaic phrasings updated as necessary), and about one quarter newly translated.

All the documents are listed in the Table of Contents.

If you would like to request a free exam copy for adoption in a course, please go to the website of Oxford University Press.

The Silk Road was already the best introduction to the reality behind this commonly used phrase. With the new documents, this version gives an even more vivid picture of how the ‘Silk Road’ actually functioned. It is perfect for the classroom.“The myth of the ‘European Middle Ages’ dissolves in the ocean currents and trade winds of this stimulating account of early global connections. Bolstered by facts and enlivened by intriguing theories, Hansen’s book presents a world of objects, ideas, people, animals, and know-how constantly on the move. A brisk and refreshing trip for us all.

— Christopher P. Atwood, University of Pennsylvania

In 2013 the International Convention of Asia Scholars recognized The Silk Road: A New History as the best new book about Asia for teaching the humanities. That is no small praise, and I could not readily agree more. Indeed, for anyone who teaches the Silk Road–or Asian or world history–this updated version that includes a remarkable array of original sources is an absolute boon. Not only because it is beautifully written and cogently offers up a magisterial overview of Inner Asian history up through the Mongol conquest, but also, more importantly, because it weaves into its narrative the excitement of discovery that lies at the heart of the humanities.

— Johan Elverskog, Southern Methodist University

The Silk Road Gallery

Dried Silk Flowers from the Astana Graveyard

Turfan Excavated from a tomb in 1972, these brightly colored artificial silk flowers, 12.6 inches high, testify to the extraordinary conditions of preservation at the oasis of Turfan, Xinjiang, in northwestern China.

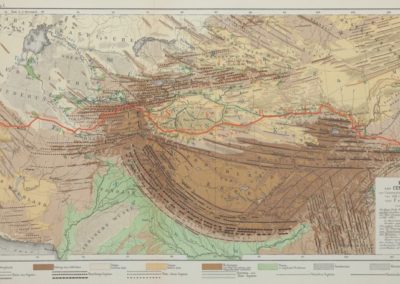

How the Silk Road Got Its Name

The German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term “Silk Road” with the publication of this map in 1877. Before this date, people referred to the route as the road to Samarkand (or whatever the next major city was).

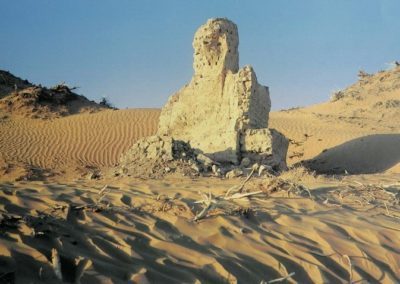

Ancient Niya

Worn by the centuries, the outer layer of Niya’s stupa has been stripped away, revealing the bricks underneath. Wooden documents found at this site are a treasure trove of information about life on the Silk Road in the third and fourth centuries (Wang Binghua).

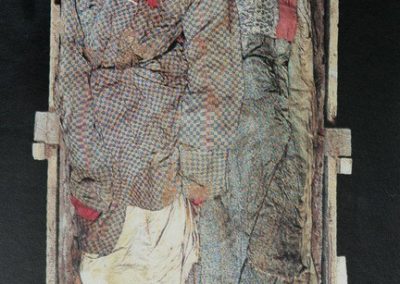

A Coffin from Niya

This Niya coffin holds a couple: the man, on the left, his wife on the right. With a total of thirty-seven richly woven silks dating to the third or fourth century C.E., the tomb is one of the richest textile finds at any Silk Road site (Wang Binghua).

Buddhist Caves at Bezeklik

This once-remote Buddhist retreat is now a major tourist destination for those visiting Turfan.

When Rivers Flowed Through the Taklamakan Desert

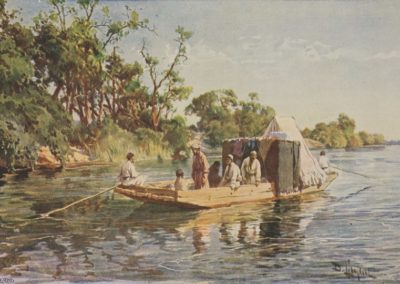

Most riverbeds in the Taklamakan Desert today are bone dry, but in 1899 the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin used this 38-foot boat to explore the waterways of the region.

Tang Barbie

When this 7th century Chinese beauty was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the staff nicknamed her “Tang Barbie” because she was the same height as the children’s doll and every bit as fashionable. Her arms are made from recycled paper that turn out to be important documents from a pawnshop.

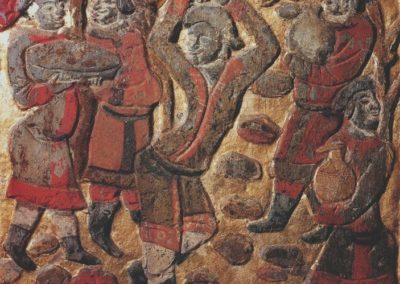

Silk Road Dance Party

The swirl, introduced by the Sogdians, was performed all along the Silk Road by men and women alike, and described by contemporaries as fast-paced and exciting. This painted stone panel comes from the tomb of a Sogdian headman in Xi’an who died in 579 C.E. (Yang Junkai).

Zoroastrian Art from Xi’an

This Sogdian tomb has a typical Chinese stone tomb entranceway with Zoroastrian art above the doorway. Zoroastrian imagery found in tombs like this is much more detailed and informative than anything that survives in the Iranian homeland of Zoroastrianism (Yang Junkai).

The Tomb of Xinjiang’s First Islamic Ruler

This tomb-shrine of the first Karakhanid king to convert to Islam, Sultan Sutuq Bugrakhan, is among the most venerated sites in Xinjiang (Mathew Andrews).

Woman Praying at the Tomb of Imam Musakazim

Here a woman kneels in prayer before the tomb of the imam at Musakazim Mazar, which is decorated with multicolored flags with quotations from the Quran and sheep carcasses (Mathew Andrews).